Theater of the Absurd

or, How a Dysfunctional Design Team Became a Case Study in Chaos

Chaos, Curiosity, and Hard Won Clarity:

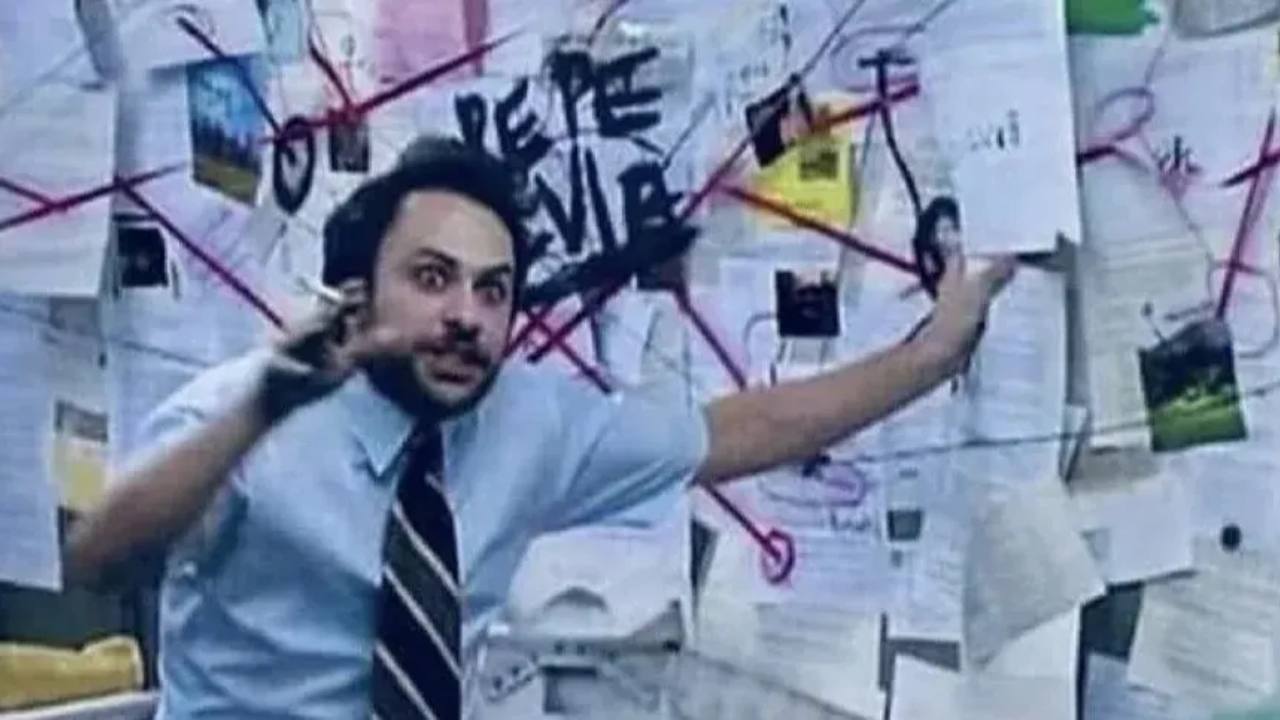

During this past week, I was situated at a veritable nexus of human creativity and dysfunction that is, in the midst of a design team that felt less like a collaboration of concerned professionals and more like a three-ring shitshow.

The experience would be best captured as a kaleidoscope of missed connections, simmering tensions, and flashing glimpses of brilliance.

As a facilitator, theater producer, educator, and conflict resolution specialist, I’ve trained to find patterns in chaos, to hold space for discordant voices, and to wrestle insight from the jaws of emotional entropy. But this week, the dysfunction was so palpable it left me raw, humbled, and ultimately enriched with new lessons about the art of collective creation.

Psychologists have long examined the dynamics of dysfunctional teams, citing unclear goals, misaligned expectations, and a lack of effective communication as a few of the top reasons groups fail.

One study found that "task conflict" may actually boost creativity in some very specific instances, but only when combined with high levels of trust and effective communication (De Dreu & Weingart, 2003).

Unfortunately, when the level of trust is low, as it was in the early days of our group, even the tiniest disagreement can quickly escalate into nonproductive conflict.

Scene One: A Room Full of Locked Doors

Walking into the literal bordello that would be our shared workspace and living quarters for the week, I contemplated the complex series of events that led me to this exact moment in my life.

The inexplicable decisions and circumstances outside of my control that wove an imperfect tapestry of what-the-actual-fuck on my path to the present. With the serendipity of that coalescence, I channeled sonder. Each of the ten other humans in attendance held a similarly complex universe of tomfuckery landing them squarely in my own present.

Together, we had the immense talent of unbearably enthusiastic people coming together with the apparent aim of creating a piece of immersive theatre on trauma and consent. From day one, as it unfolded, (maybe unraveled is a better word) we began running into doors between us, locked, and none of us had thought to bring the keys we’d thought unnecessary encumbrances to our travel.

The "locked doors" phenomenon in collaborative environments can be explained through the concept of psychological safety, popularized in landmark research at Harvard by Amy Edmondson. According to Edmondson, psychological safety is "a shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking".

Without it, participants are unlikely to share ideas, voice concerns, or fully engage emotionally and intellectually, locking themselves behind closed doors. Reflecting on our early interactions, I could see how the lack of shared language and mutual understanding had eroded our psychological safety.

This team was over qualified by all accounts, highly educated, skilled, experienced, and technically capable in all of the fields we could hope to draw from.

Our charge was ambitious: to design a one hour theatrical experience that could illuminate the complexities of trauma, consent, and communication in sex positive spaces. The stakes were high, not only for the project but for the group itself, a highly combustible mix of seasoned experts, fresh contributors, and a handful of "wild cards" whose presence felt more like a question mark than an answer.

Coming from a background where structure and purpose are my driving forces, not having shared goals or language felt like being dropped into a maze without a map. As the designated navigator on most ships I find myself on, I felt deeply awkward… I could chart a path through the open waters, but it wasn't my place. It wasn't my job.

So, despite the constant pull, and impulse to demonstrate value, to invite structure, to impose order, I made a decision. To surrender myself to the chaos, and choose to weather the storm as a member of the crew.

Often large problems can't be solved without breaking out of our conventional pattern thinking mold. But without an effective framework or mutually understood roles for us, the group faltered and tripped its way through assumptions from mismatched knowledge bases and unsaid expectations.

Theater of the Absurd

It is here that I learnt that dysfunctional teams are themselves theaters of unmet needs, unsaid assumptions, and unforgotten hurt. We enacted all our parts this week, some clung to hierarchies, straight and rigid, others refused all structure. The explosions in emotion unsolicited and extempore like monologues, again, left others picking up bits so collaboration could proceed over the fallen trees of hurt or misunderstanding.

What struck me most was how quickly misunderstandings escalated. Researchers have noted that teams without clear norms are more likely to devolve into what is termed "relationship conflict," characterized by interpersonal friction and emotional tension (Jehn, 1995).

Unlike task conflict, which can spur innovation, relationship conflict often results in decreased productivity and morale. In our case, the absence of shared norms magnified every minor miscommunication; disagreements about process became personal grievances.

There were moments, too, of deep hilarity and insight. One exercise involved coaching two actors as if they were boxers training for a match, their "subconscious coaches" whispering strategies and fears in their ears.

The metaphor of sparring—of stepping into the ring with both vulnerability and intention—felt deeply resonant.

We are all actors on a stage, playing the roles that society expects us to play.

-Erving Goffman

The idea of "performance" by social psychologist Erving Goffman is a good framework for understanding this exercise. According to Goffman, we are always performing roles in social interactions, balancing authenticity with the demands of the moment. The boxing match revealed how even our subconscious "performances" shape our ability to connect with others.

These flashes of brilliance were islands in a sea of disarray. Without these anchors, tension in the room could have spiraled into full blown dysfunction.

Chaos as a Teacher

Despite—or because of—the dysfunction, the week forced me to confront some uncomfortable truths about facilitation and creativity. Chaos, I realized, is not inherently productive. It can smother brilliance as surely as it can spark it. But when held with curiosity and care, chaos can become a crucible for transformation.

Research on creativity and innovation supports this paradoxical relationship with chaos. Keith Sawyer describes a phenomenon he calls "collaborative emergence," in which creativity arises in self organizing groups that encourage experimentation while providing enough structure to channel the group's energy.

“people are more likely to get into flow when their environment has four important characteristics. First, and most important, they’re doing something where their skills match the challenge of the task. If the challenge is too great for their skills, they become frustrated; but if the task isn’t challenging enough, they simply grow bored. Second, flow occurs when the goal is clear; and third, when there’s constant and immediate feedback about how close you are to achieving that goal. Fourth, flow occurs when you’re free to concentrate fully on the task.”

-Keith Sawyer

This insight resonates with my own experience: when chaos is allowed to run unchecked, it can become paralyzing. But when framed within intentional boundaries, it can become a source of unexpected breakthroughs.

One was when Dr. Robitaille, a trauma expert, introduced us to a collective frame of reference for understanding the responses to trauma. Naming how our bodies and minds go into fight, flight, freeze, or fawn modes in response to overwhelm really helped us understand just how it was showing up in our group.

This gave us a foothold a way to navigate the sea of emotions and conflicting agendas that had derailed our process.

Dr. Robitaille's approach is a mirror of the principle of trauma informed care, which centers on the notions of safety, trust, and collaboration. The SAMHSA points out that creating a trauma informed environment means being well versed in how trauma influences the lives of individuals and using that understanding to build practices that do not retraumatize. Because we based our discussions on this knowledge, we were able to move past reactive conflicts toward a more contemplative, empathetic way of collaboration.

This shift also echoed the power of vulnerability in leadership. Naming difficult emotions and dynamics is a form of courage that creates space for growth. In our case, naming the chaos didn’t resolve all our challenges, but it provided a shared language that made those challenges easier to confront.

The Myth of Emergent Design

Perhaps the most important understanding for me was how structure facilitates the emergence of creativity. There is this romantic view that a bunch of talented people get thrown in one room and stuff magically happens; this week showed differently. Without clearly defined roles, clear boundaries, and shared purpose, even the most skilled flounder.

This misunderstanding is partly founded on a very misguided view of emergent processes. Complex systems theory as explained by Donella Meadows demonstrates that emergent processes emerge from the interactions of individual elements interacting within a well defined structure. There, pattern can emerge organically.

“A system* is an interconnected set of elements that is coherently organized in a way that achieves something.”

Donella Meadows

Where structure is absent, emergence often gives way not to emergence but to entropy, a breakdown in coherence and direction. In our group, the lack of shared goals and clearly defined roles created a vacuum that chaos readily filled.

Emergent design, I’ve come to believe, isn’t about abandoning structure. It's about creating the scaffolding that allows spontaneity to flourish. We set the stage so that when the actors step into the spotlight, they’re not performing into the void but into a shared understanding of what they’re trying to build together.

Structure does not have to hamper creativity; it can and should inspire it by directing people on the ways to take meaningful risks, outlining the stage and its unique constraints.

Scene Two: The Anatomy of Dysfunction

The group dynamics we encountered were not just different opinions or styles; they were a whirling dervish of unsettled pasts, professional egos, and cross cultural misunderstandings. Sometimes, it seemed like we were all speaking different dialects of the same language, where subtlety caused major disruptions.

Conflict in teams is well documented in organizational psychology, and Tuckman's model, “Forming. Storming. Norming. Performing.” provides a useful framework for our tribulations. A team would normally be plagued by tussles around role, responsibility, and power at the "storming" stage.

Ours appeared to be stuck in this cycle of endless conflict, unable to attain the level of uniformity and coherence that would lead us into "norming" and "performing.".

For example, one participant—a veteran theater director—wanted to anchor our work in physical biomechanics, a method harking back to Meyerhold's lessons. Another member insisted on emotional safety above all, calling for exercises that require gentleness and introspection. These were by no means necessarily incompatible approaches; without a common framework, however, they became points of dispute rather than synthesis.

Internal integration should take place inside the teams where the diverse viewpoints would be united within one big idea or concept. In our case, instead of integration, there was fragmentation with each group fighting for its own priorities.

As names have power, words have power. Words can light fires in the minds of men. Words can wring tears from the hardest hearts.

-Patrick Rothfuss

The Power of Naming

The power of naming that saved us, time and again. Naming the emotions in the room. Naming the dynamics at play. Naming the shared values we were striving to uphold, even when it felt like we were moving in opposite directions.

This naming practice, borrowed from trauma informed facilitation, became our lifeline. When someone was triggered, we paused to name what was happening not as a failure, but as a natural response to the challenging work we were doing. When the group veered off course, we named the distraction and gently guided it back. Naming gave us clarity. Clarity gave us momentum.

This is also supported by the psychological research. Emotion regulation studies indicate that naming emotions helps a person manage their intensity and reduces impulsivity.

By naming what we were feeling, we created space to acknowledge those emotions without hijacking the process.

The Boxing Match

Perhaps better still was the "boxing match" game that will likely remain one of the most memorable exercises of the week.

Started in an almost joking fashion, presented by a participant professing no experience whatsoever in the world of immersive theatre, but boundless interest in conflict dynamics: simple setup where two people facing each other, the subconscious mind brought alive by the "coaches" offering counsel and color commentary.

It was like watching this microcosm of the week unfold.

The "boxers" hesitated, fumbled, and at times froze, but as they began to listen more deeply to the subconscious voice within them, something magical occurred: They started to move with a purpose. Intentional action developed, their interactions with each other real. Messy, it wasn't perfect, but it was real. And in that realness came the beauty.

“When you feel like quitting, remember why you started.”

-Life

This exercise is in line with the principles of Augusto Boal's Theater of the Oppressed, which uses theater as a rehearsal for social change. Boal's techniques invite participants to take on roles, confront conflicts, and rehearse alternative ways of acting in the world. The boxing match was not just an exercise in performance but a tool for exploring the subconscious drivers of our actions our fears, desires, and vulnerabilities.

The power of this exercise also lies in its connection to embodied cognition, a theory that our bodily actions and movements shape how we think and feel. By stepping into the "ring" and physically embodying conflict, participants tapped into insights that may have remained buried in a purely intellectual discussion.

The boxing match became a metaphor for our entire process. We were all sparring, sometimes with each other, sometimes with ourselves. But when we allowed our subconscious "coaches" to speak, when we listened to the undercurrents of our fears and desires, we found a way forward.

Scene Three: Lessons Learned

By the end of the week, I was struck by what I was taking away—less from the lessons of facilitation than from leadership, collaboration, and the messy, beautiful work of creating something together.

Structure Liberates

Chaos may be the birthplace of creativity, but structure is the midwife. Without clear boundaries and shared language, our group floundered. When we introduced even modest frameworks—like timeboxing discussions or defining roles—we saw an immediate improvement in our ability to collaborate. Progress in meaningful work is one of the most powerful motivators. Clear structure helps teams see their progress, fueling both creativity and morale.

Conflict Is a Feature, Not a Bug

With any group, but especially with one as diverse as ours, conflict is not something that can be avoided. Rather, it is how we navigate it curiously and with care. And by framing conflict not as a problem to be solved but as an opportunity to learn, what could have been moments of tension became moments of growth. Well managed conflict can help a team's performance and innovation by bringing in various perspectives and building trust in the shared capacity to hold disparate viewpoints.

Empathy Is a Superpower

Over and over, I saw how empathy the simple act of truly listening could defuse tension and build bridges. When someone felt heard, they became more open, more generous, more willing to compromise. Empathy didn't solve all our problems, but it created the conditions for solutions to emerge. Empathy is not a passive act but a courageous choice to engage with others' emotions.

Trust the Process, and Improve It, Too

There's a fine line between trusting the process and clinging to dysfunction.

This week taught me to trust in the group's collective wisdom but also to advocate for changes when the process itself got in the way.

Emergent design works best when it's paired with thoughtful iteration.

“Organizations learn only through individuals who learn. Individual learning does not guarantee organizational learning. But without it, no organizational learning occurs."

Peter Senge

Adapting the process based on real time feedback was key to our successes.

Finale: The Doors We Open

As I gather my notes, I can't help but feel grateful for the chaos, the conflict, the hard won clarity that emerged from it all. This week was not what I expected, but it was precisely what I needed.

It reminded me that some locked doors are an invitation to find the keys that will open them. In the end, our group did create something remarkable: an outline for an immersive theater experience that captured the nuances of trauma and consent in ways I never could have imagined on my own.

But more than that, we crafted our own set of keys for navigating conflict, for building trust, and for unlocking the potential of even the most dysfunctional teams.

There is no perfect process, just as there is no perfect team. Yet, if this week taught me anything, it's that perfection isn't the goal. The journey is connection, understanding, and the willingness to step into the chaos together. That's where the real magic happens. The goal is walking that journey together in the most productive way possible, arriving at the intended destination with a story worth telling and, when applicable, a product worth sharing.

That requires the right team, the right structure, and the right tools to make the magic my life has sculpted me to perform.

Looking Forward to You,

Responses